Fact & Folklore

Reference

- Coventina's Well: A Shrine on Hadrian's Wall by Lindsay Allason-Jones and Bruce McKay, is the report on the excavations at the site. It was published by the Trustees of the Clayton Collection in 1985. It has a scholarly introduction to the history of Coventina, and a thorough, exhaustively detailed, and illustrated catalogue of the finds. This book is available from Amazon but you can get it much less expensively at Oxbow Books, an online bookstore that specializes in books on archaeology and history.

- An excellent resource on goddesses from a myriad of cultures can be found at Thalia Took's site, which apart from some delightful art, houses OGOD, a.k.a. the Obscure Goddess Online Directory! Check it out; it's fabulous.

Folklore

Most of what is known for sure about Coventina was revealed by the archaeological investigation. But perhaps some remnants of her influence remain, running through folk memory like an underground stream.

- Names of the city of Coventry and the Tyne river

- The dedication of wells

- Coventina in myth?

- Coins in the water

Names of the city of Coventry and the Tyne river

When Coventina's temple at Carrawburgh was destroyed, her name was forgotten for over a millennium. Or was it?

The currently popular theory is that the city of Coventry takes its name from Coffa Tree, harking back to a leader called Coffa who held court under a tree. Or perhaps, from 'cof' meaning memorial and 'tree' meaning town settlement. However, it is entirely possible that Coventry was named after Coventina.

Michael writes: "Born in Tile Hill on the outskirts of Coventry, I spent nearly thirty years in the Coventry area and, since childhood, did a lot of historical research over that time. My belief is that the medieval 'Coventry=Coffa Tree' theory is rubbish and unfounded. Coventry goes back a long way, long before those times. Its Pagan and Roman links are far more important and can still be seen in local place names such as the district named 'Coundon' which means 'meeting of the waters', and the name 'Coventry' itself. It makes sense that Coventry is named after the water nymph/goddess 'Coventina'. Being a 'Coventrian', born and bred in Coventry, I have long believed Roman roads in the area (Foleshill Road, Warwick Road, London Road) converge on Well Street and Jordan Well."

Pauline writes: "Coventry perhaps derives from a word 'couan' meaning 'where the waters meet' (the river running through it which is now the Sherbourne was once called the 'Cune'). That feels like a strong possibility and, in that case, it is highly likely that the name Coventina came to be linked to the place."

Others have theorized that the name Coventina is related to the name for another famous river in the region, the Tyne. Maybe one ancient spelling of her name was Coventyna. This may seem far fetched but in fact, the worship of goddesses was once so ubiquitous, and they were held in such high esteem, that naming rivers, cities and even countries after them was commonplace.

For example, Holland is named after the goddess Holle, Ireland is named after the goddess Eriu, Scotland is named after the goddess Scotia, and Britain is named after the goddess Brigantia, who was known as Brigid in Ireland. Most of the people who live in these areas are not aware of the origins of these place names. The most well known example of a place or city being called after a goddess, is of course the naming of the Greek capital city Athens after Athena. So perhaps it's not so unlikely that Coventina could have lent her name to both the city Coventry and the river Tyne.

Pauline also quoted the following from a book called Coventry History and Guide by David McGrory, published in 1993:

"One local legend states that the Roman general Agricola stopped here, built an encampment on Barr's Hill and named the nearby settlement Coventina. The interest of this legend lies in the fact that Coventina, a Celtic Romano water goddess, was virtually unknown in this country until her only shrine was discovered at Carrawburgh in Yorkshire in the 1890s. Coventina, being a water goddess, would have been at home in Coventry with its rivers, pools and springs: she was depicted naked or half naked holding a plant and pouring water from a jug or urn. An ancient coin-like object was discovered near the Priory Mill in New Buildings in the last century. This had on one side, a woman pouring water from a jug, and on the other a naked woman with a flower at her feet. It is possible that this has some connection with the legend."

The dedication of wells

Naming wells after sacred or respected characters from local mythology is a very old and widespread tradition in many cultures.

For example, have a look at this Lady's Well at Holystone in Northumberland.

Near my own home in Ireland, there are three holy wells within walking distance, and their waters are believed to have healing abilities. All three are now named after Christian saints, but I wonder who, if anyone, they were named after before Christianity arrived in Ireland.

Tim Midgley writes: "Although I am not a follower of Paganism, I can draw lines between Coventina's well at Carrawburgh and that of the so-called 'Robin Hood's Well' near Skelbrooke, South Yorkshire. This well was a crystal clear spring in an area of chalybeate springs. These do not look pleasant because of the siderite or iron carbonate in the waters which makes them look rusty, and would be no use for washing! Because chalybeate springs were often associated with coal measures, they were often sulphurous too (sulphur dioxide and/or sulphur dioxide). Thus the well near Skelbrooke on the Roman road north to York and beside a Roman auxilliary fortlet could well (ha!) have been a sacred Roman site to a water goddess similar to Coventina."

Check out Tim's site for more information and photographs of Robin Hood's Well. He even has a page devoted to Coventina's well, which makes some excellent points, not least of which is that the co-existence of several religions at the Carrawburgh site has something to teach us about religious tolerance.

Coventina in myth?

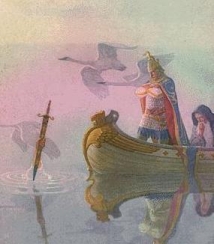

You may have read or seen movies based on the legends about King Arthur. In them, Arthur receives a sword called Excalibur from a mysterious Lady of the Lake. This Lady may have been Coventina.

According to the legends, when Arthur lay dying, he asked his most faithful knight, Belvedere, to take Arthur's sword and return it to the Lady of the Lake. The knight fulfilled Arthur's dying request by flinging the sword into the water, where the Lady, seen only as an arm reaching out of the water, caught it and took it back.

Swords have been found in bodies of water many times, all over Europe. The swords in this photograph, for example, were found in rivers in the North of England. As swords were extremely high value items, it is unlikely that they would be simply thrown away. Instead, it could be that they were mislaid, or that they were deliberately placed in the water to put them beyond an enemy's use.

But it could also be an ancient way of making a sacrifice to the goddess of the waters.

Coins in the water

Making a wish while tossing a coin into a wishing well, pool or fountain, is a tradition that goes back millenia and is as common as mud. Everyone's probably done it at one time or another.

The best known example in popular culture is to do with the Trevi Fountain in Rome, a beautiful baroque fountain that marks the end of an ancient aqueduct. Dropping a coin into the Trevi fountain is supposed to ensure that the owner will return to the city. The custom is so well known that about 3,000 euro is retrieved from the fountain each night and donated to charity. There's even a movie, Three Coins in the Fountain, which refers to this practice.

Some scholars believe that the tradition of tossing a coin into a pool or fountain while making a wish is another folk memory of worship of Coventina. It's impossible to say for sure. What is certain is that many coins -- more than thirteen thousand -- were found in Coventina's well when it was excavated. Dating of the coins shows that the practice of placing coins in Coventina's well lasted for generations.

This article discusses the tradition of well wishing with coins from an anthrological point of view, and refers to Coventina's well.

Websites

- The Megalithic Portal. The "Hitchhikers' Guide To Ancient Sites" has an entry for Coventina's Well, including excellent links to online maps of the archaeological site and map references, perfect for hillwalkers and explorers.

- Wikipedia has an article on Coventina.

- Celnet has a brief entry on Coventina in its database of Brythonic Celtic deities.

- Vindolanda is a museum and visitors' centre based around the well-preserved ruins of one of the forts on Hadrian's Wall. It has reconstructions of buildings of the period, including a temple.

The Story of Coventina · The Seventh City upon the Wall · Coventina in Context · Fact & Folklore

Images · Archaeological Site · Spirituality

Other Goddess Sites · Fanlisting · Contact · Home

Graphics © FMG · Valid XHTML & CSS · Pro standards & access

All original content © Tehomet 2005